“The number one rule of cartographia was that if you could not observe a phenomena, you were not allowed to depict it on your parchment”

“The number one rule of cartographia was that if you could not observe a phenomena, you were not allowed to depict it on your parchment”

-The Selected works of T.S. Spivet p.32

I’m excited to be traveling with the Polaris Project group again this year. I’ve been a part of this project since the early days, and the memories and relationships built over the years are among the highlights of my career thus far.

People often ask me: Why do you get to go on these trips? You’re a data analyst and a map maker, not a field scientist! My immediate answer is, well, of course every expedition needs a good navigator. But probably a more appropriate snark-free answer is that I think there is great value in having a spatial person, like myself, with a laptop packed full of data at any basecamp/field site.

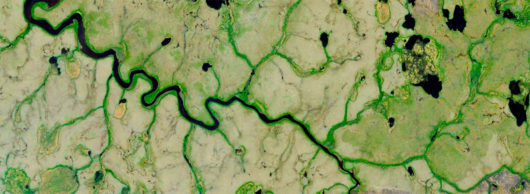

On the tundra there are no cell connections or wifi, which means of course, no Google Maps… and your Uber app isn’t likely to get you very far. Instead, we rely on custom made maps from a plethora of public and private satellite and geospatial resources, home-crafted and brewed on the fly, sometimes while sitting in the dining tent around breakfast or late into the evening after dinner. Likewise, I believe it is immensely valuable to be able to do geoanalytics as the field work is actually happening and not weeks later back in Woods Hole (as is often the case).

It’s not uncommon for me to answer questions such as: Can you show me five randomly selected sample locations in each landcover type between both burned and unburned tundra? Can we find a river where the headwater catchment is more than 50% burned? The list goes on…

Being spatially efficient is practical. This is especially true during an elaborate field campaign with many participants trying to stick to a limited budget. On “helicopter days,” for example, we have a visiting helicopter pilot from the village of Bethel who comes to shuttle researchers to and from field sites that cannot be reached by foot or boat. After reviewing the maps and spatial data, we can make plans for each research party (name of participants, destination, targeted land cover type, number of stops, etc.) well in advance. When the helicopter arrives, we hand the pilot a short list of coordinates and an overview of the day’s plan and we’re off. Combining this spatial plan with the pilot’s knowledge of the region allows us to move people to/from their field sites as efficiently and safely as possible.

Over the years, I’ve visited many different WHRC field study sites in the Arctic and in tropical forests. Each time I travel with a pile of local spatial data and tend to preach the efficacy of spatial awareness. Having worked with hundreds of scientists, I’ve now come to favor being a part of the teams that can get me out to the field and away from my desk. Not just for the adventure, but also to build experiences that’ll inspire me to do my best work. How can you map a place you’ve never seen or explore the relationships between a selection of geographic features if you don’t know how they exist in their natural state?

Did you know that permafrost isn’t actually blue as so many maps often depict? And, although the tundra can often be white, it also can be a brilliant green in a wet year or a patchwork of browns in a dry year. I’m looking forward to meeting and working with this year’s participants, the 7am analytics sessions around the breakfast table, the 11pm map reviews, and just seeing the tundra again and what color it’ll be this year.

— Greg Fiske, WHRC Senior Geospatial Analyst and Research Associate