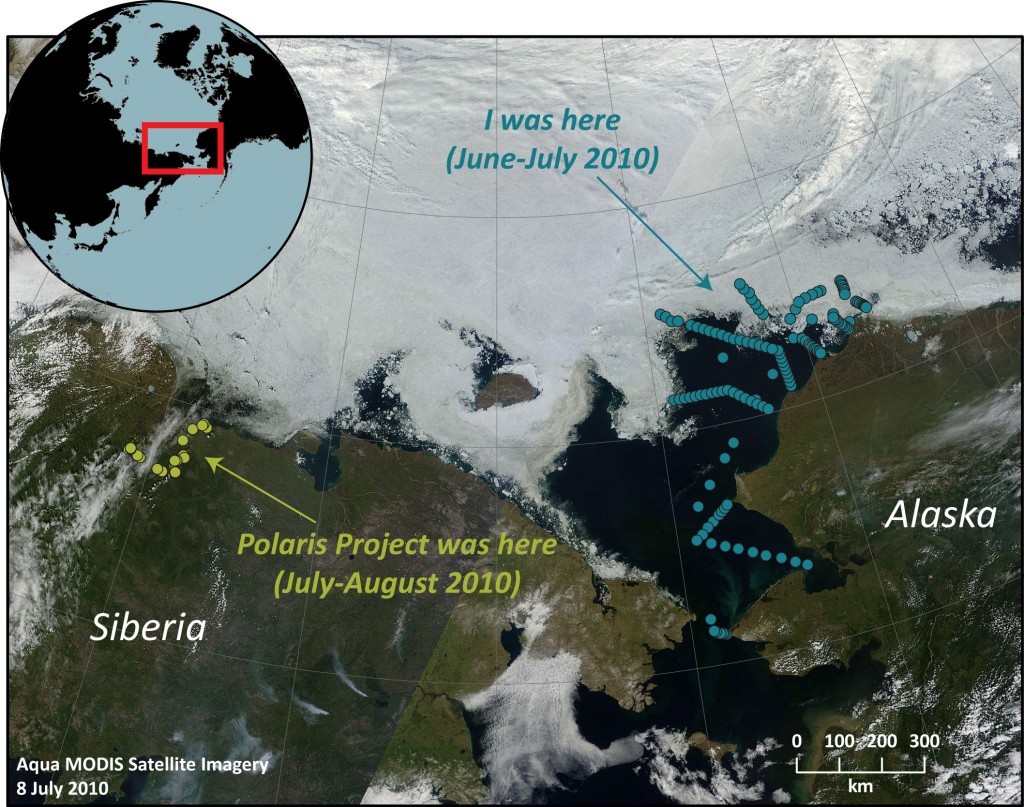

Unfortunately not all of the PIs were able to travel to Cherskiy for the Polaris Project 2010, myself included. I greatly missed being at the Northeast Science Station and being in the field with such a fantastic group of scientists and students. As you may have read from others already, the Polaris Project experience has been a life-changing, profound experience for professors and students alike – both personally and professionally – and I am no exception. However, in addition to conducting research on the impacts of climate warming on terrestrial and freshwater biogeochemistry (as we do with the Polaris Project), I also have active research projects investigating the impacts of climate warming on Arctic sea ice. For the past six weeks, I have been onboard the US Coast Guard Cutter Healy (a 420 foot icebreaker) in the Chukchi Sea, northwest of Alaska. In fact, I’ve really only been ~600 miles away from the Polaris Project folks this whole time (about the distance between Seattle and San Francisco). Here you can get a glimpse of what the Healy sees on her many Arctic voyages, every hour on the hour. Below you can see how sea ice was situated in early July 2010 in relation to all our sampling locations during both of our field seasons.

As part of NASA’s ICESCAPE mission on the Healy, I and two of my Ph.D. students from Clark University (Christie Wood and Luke Trusel) were coring sea ice, collecting samples from the under-ice water column, and measuring light penetration at different wavelengths through the sea ice and through the ocean waters below. All of these parameters will give us insight into how expected future sea ice declines will impact the biology and biogeochemistry of one of the most productive marine ecosystems in the world. Conducting research onboard an icebreaker is a unique experience – for one, most of our group’s research was carried out by simply walking off the ship (in the middle of the ocean, mind you), straight onto the sea ice below.

June and July is an incredibly dynamic time of year in the Chukchi Sea, when sea ice begins to degrade, melt ponds form on sea ice surfaces, and hot algae blooms run rampant throughout the region. At our sampling stations, we were able to investigate both melt ponds (which function as “skylights”) and bare white ice surfaces (which shade light much more effectively), each impacting the biology and biogeochemistry of waters below to different extents.

The Chukchi Sea is also home to some of the most charismatic mammals on the planet (which are at the top of a food chain that the presence and seasonality of sea ice afford), to include polar bears (now deemed “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act) and walruses (which were just just petitioned under the Endangered Species Act in 2008). These “ice-obligate” species have been given particular attention owing to recently observed declines in Arctic sea ice. We were lucky enough to see a collection of these critters, to include a mother polar bear and her three cubs (likely two seasons’ worth).

So while I am missing my Polaris Project compatriots this summer, each of us was able to discover a small puzzle piece towards understanding an Arctic region so dramatically impacted by climate change. Here’s to furthering Arctic research – wherever you happen to be!